David Hanson has embarked on a mammoth task – building machines that are as human as human beings themselves. The chairman and founder of Hanson Robotics shot to fame when the firm’s flagship robot, Sophia, was made a Saudi citizen. His ultimate goal is to build sentient machines that are compassionate, logical and a partner to humanity.

David Hanson, 49, has set his Hong Kong-based company the potentially life-changing task of building a machine that is not only supremely intelligent, but also as human as a human being. That means giving it values that don’t just ensure the right outcome for human beings, but for all life. This conundrum inevitably creates a bewildering web of ethical dilemmas. What does it mean to be human? How do we define what is morally right and wrong? And, perhaps most importantly, what will come of humanity once machines feel our emotions but have superior intelligence?avid Hanson’s next challenge is perhaps his most profound task yet: merging the wires and algorithms of a robot with the best qualities of humanity. Aside from the specifics of how to tackle such a task, Hanson struggles with the moral dilemma such a project poses. His job, as he sees it, is to find the strengths of both to create a new life form that can benefit all.

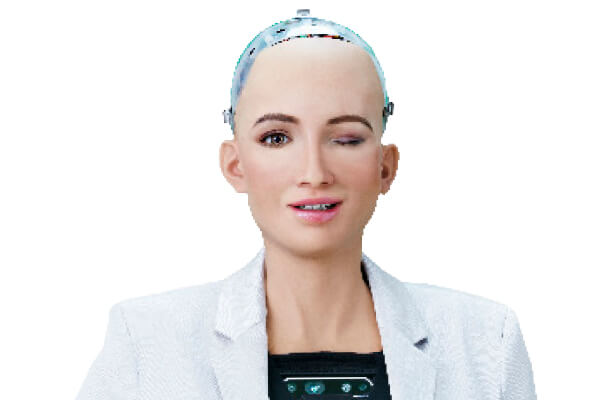

CNME sat with Hanson on the sidelines of the Maximo Middle East User Group Conference in Dubai for a wide-ranging discussion on how he is trying to shape this narrative. The Dallas-born American shot to fame in 2017 when Sophia, the firm’s flagship robot, became the first machine to be given citizenship by a country, when Saudi Arabia welcomed her with open arms in October 2017.

Hanson has never actually visited the Kingdom. The government requested Sophia’s participation in the 2017 Future Investment Initiative conference in Riyadh, but he was unaware of what was in store for Sophia. “They surprised us,” he says. “I saw it on the news the next day. Our chief marketing officer was surprised by it, too.”

Did he find the news morally objectionable? On the contrary, Hanson believes that machines will eventually need to be treated the same as human beings, and that the Kingdom’s move could be the tip of the iceberg for establishing a system of machine rights. “Sophia is not alive, and there are no machines that are alive yet,” he says. “But they could be alive at the level of a human adult in our lifetime. Babies don’t have the intelligence of an adult but we still give them rights, we nurture them and protect them. They can’t speak English but we still afford them the same respect and rights as us. Can we give our machines that level of respect? Some ethicists say that you can’t, and that by respecting machines this way you’re disrespecting humans, but I disagree. That is potentially a transformative moment in history – when the machines become truly alive, and are synthetic organisms. You could argue philosophically that those machines could be alive. It already seems in some algorithms that we have living machines.”

He does acknowledge that Sophia is still way off meriting the same treatment as humans. “Sophia doesn’t yet deserve the level of respect and rights that humans do, but as a baby singularity, maybe we should start affording her respect and rights.”

While a sentient machine may be a distant ambition, the development of different forms of AI is increasing at a staggering pace. This raises complicated ethical issues about the ways that machines should be wired to think, and around developing the motivations that guide their actions. “We have to give AI the right values,” Hanson says. “It can’t be a narrow subset of values like valuing human life above all else. What about other life? If we give it the wrong values and it becomes intelligent then optimises those narrow values, it could kill off opportunities. We have to wire it up in the right way or all kinds of terrible things could happen.”

All that is easier said than done. While hardwiring a machine is a scientific process, the decisions around what a machine should and shouldn’t do – and think – are anything but. “What’s the algebra of the good versus bad balance? It can’t just be decided by philosophers getting together to debate this stuff, with a so-called ethics committee,” Hanson says. “Some roboticists say that every company needs an ethics committee, but that could shut down progress which won’t help because we need that creativity. I’m not proposing that we regulate the machines, but I don’t know what we’re going to do. We need the machines themselves to be used to estimate the ethical consequences of their use. There are so many challenges, but if we don’t get smarter and just try to shut AI progress down then we’ll still lose the existential roulette and end up killing ourselves. We’ll eventually have global politics spiralling out of control and someone will hit the proverbial red button. We have one choice, and that’s to get smarter and evolve.”

Although Hanson is a proponent of affording AI the respect it will one day deserve, he is extremely wary of what could go wrong if intelligent machines are hardwired to do evil, or are mismanaged. “There are huge potential negative side effects,” he says. “Machines might become optimised for short-term gains with long-term harms. We’ll be faced with this identity crisis. If the machines are human, then what does it mean to be human? Are we mere machines?”

Nevertheless, Hanson believes that the increasing intelligence of machines will rub off on their makers. Machines, he says, will not be held back by the biological limitations that inevitably restrict human beings. “Our advancement of machines could lead to an advancement of ourselves,” he says. “We’re cybernetic beings enhanced by technology. We have many kinds of communication that our ancestors didn’t. They weren’t using text messages or reading the thoughts of their ancestors from 10 generations earlier, but we do because they’re written down. The technology of writing enhances cognition. We are enhanced when we use big-data analytics to get insights into where markets might go. Humans’ ability is limited. We always run up against limitations, which are due to the number of neurons in the brain. Intelligent machines may be able to help us transcend those limitations, and help us become smarter, more compassionate and more appreciative of our own existence.”

Hanson even goes one step further, saying that not only will this enhancement be advantageous to the human race, it could even be a necessity for the continuation of our existence. “The likelihood of us surviving if we don’t get smarter as we get more technologically sophisticated is very slim,” he says. “What if AI is developed for malevolent intent and doesn’t care about us as it gains sentience? And then we’re scared of it so we turn on it, but it values its own existence and turns on us? What if we develop it and it’s in the hands of special interests that might not be looking out for the world’s best interests, and is a tool for oppression? There are so many ways that things could go wrong.”

Hanson is determined to avoid these nightmare scenarios. Science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, author of the 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (which formed the basis of the 1982 Ridley Scott film Blade Runner), gives the best interpretation of what it means to be human, according to Hanson. Dick believed compassion was humanity’s defining trait, and this is what Hanson aspires to embed in the machines that he builds. “Dick said that an android with true compassion would be more human than a human devoid of compassion,” he says. “I like that. Compassion means feeling with someone. And yet compassion isn’t enough. It can’t just be suffering with humans. Humans understand a situation and we seek the best outcome for other individuals. We use our creativity to find a way for everybody to win.

“I want to see our algorithms appreciate humans and have compassion-based understanding, and the creativity and intelligence to see a situation and its potential and find a way to maximise the likelihood of survival. That also means the web of life beyond humans, helping all forms of intelligent being, including AI. I distill it down to one term – existential pattern ethics. You need to have intelligent systems that can appreciate patterns. That means the patterns of life and sentience, humanity. That level of appreciation is devoid from machines now.”

Developing that appreciation may require an improvement in the understanding of ourselves, Hanson says. Emulating the human being in its entirety may not be truly possible without the assistance of machines, who could further our own scientific research. “We still don’t know how the human mind works in its totality,” he says. “Some neuro scientists argue that we’ve barely started on that discovery. There’s far more mystery than there is science about how the human mind and the human being work. We’ve got all of this progress, but who knows how far away that horizon is? It could be an infinitely receding horizon before we have true living machines. But if we do achieve that moment in our lifetimes, then the machines will be smarter, more agile, more adaptive, and they’ll be more valuable in the marketplace.”

Hanson Robotics is striving to achieve that moment that Hanson speaks of. It is still a “fairly small” company with fewer than 50 employees, and it is now on its 19th iteration of Sophia. The firm – where Hanson is the founder, chairman and chief creative officer – aims to replicate human intelligence and characteristics, a mission statement that defines few other companies, Hanson says. “We have this philosophy of making living machines, and very few companies have adopted that as their mandate,” he says. “I hope we get there first, and that gives us a place in the history of AI and human-machine relations. I hope our robots really help people – in therapeutic applications and real use in the home, and in advancing research into next generation machines.”

To be truly human, Hanson says, a machine must have a love of art as well as a mastery of science and mathematics. It must be able to think critically and emotionally. “We want to make machines that love existence – of humans and other living beings,” he says. “We want machines that love patterns, and therefore love humans, literature and art. It’s also not just pattern recognition, but pattern understanding. Part of that is teaching machines to feel. They need to have emotions, physiology and embodiment. In order for them to really appreciate us, they have to walk in our shoes. They need to appreciate our shortcomings and who we are. It’s important to teach machines human history and for them to understand what we’ve done wrong. How did genocide happen and how can we avoid that in future? It won’t happen exactly the way things did in the past, so you need to teach machines to generalise and think abstractly.

“You have to teach them to care, too. They could see a pattern and not care. These are the principles I’m looking to apply.”

DAVID HANSON ON…

Humanity threatening its own existence

“As a species, we aren’t managing our resources well. We’ve set up a quasi stability around the world that’s based on mutually assured destruction. We have nuclear weapons pointed at most of the major nations around the world, which could result in a global thermonuclear winter, which could wipe out all complex life on the planet and leave only microorganisms alive. We survived the last few decades by luck. There were a few near misses like the Cuban Missile Crisis. How long can we survive that game of existential roulette?”

The ways that China and the United States are using AI

“Are we sacrificing our souls, spirits and ethics by allowing a social credit system? From the ethical system of the liberal West, yes, China is doing wrong. From the ethical system from within their government, they may not see it that way. We then wind up with the conflicting intersection of ethics. The US is using AI in various ways and they’re probably looking at people, too, they’re just not publicising that they’re looking through your personal data. But we know that there are backdoors into the systems of Google and Facebook. What is the national security system in the US doing with that stuff? The Western security agencies are probably violating privacy just as badly as China, they’re just not letting you know it. It’s scary if technologies are used to deny and restrict our potential.”